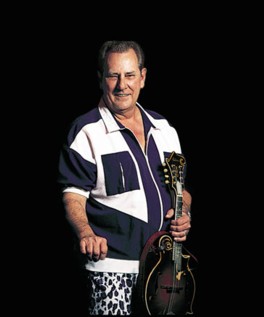

John Duffey

The following tribute to John Duffey was written by Dudley Connell for Sing Out! Magazine.

When John Duffey died on December 10, 1996, he left an imposing and very important forty year musical legacy.

When John Duffey died on December 10, 1996, he left an imposing and very important forty year musical legacy.

John was a big guy with commanding stage presence. With his 1950s style flattop hair cut, multicolored body builder pants and unmatching bowling shirt, he left an indelible impression. When he arrived at the stage with his trademark mandolin and home made cup holder, complete with a special clip ready to attach to an unattended microphone stand, you knew John was ready to go to work.

His huge hands flew expertly across the neck of his tiny mandolin at a speed that seemed impossible. He made it look so easy. John would occasionally invite other players in the audience to sit and play his mandolin. They invariably found its high and tight action intimidating. Akira Otsuka, a long time Washington area player and John Duffey disciple, once looked at me after attempting a break on John’s mandolin and asked, “How does he play this thing?”

John’s most remarkable instrument, however, was his powerhouse tenor voice. There has never been any voice in bluegrass more unmistakable or capable of such range as that of John Duffey’s. It seemed to ignore human bounds. His voice could range from the soft and delicate, ‘Walk Through This World With Me’, to the aggressive and powerful, ‘Little Georgia Rose’. Even at age 62, his voice was both challenging and inspiring to accompany.

John Duffey was as well known for his entertaining stage swagger as for his incomparable musical abilities. He was like a loose cannon on stage. Unlike many performers who have been entertaining for a long period of time, John did not work from scripted stage patter. Anything and anybody was fair game. There were many times John would hook onto a unsuspecting heckler in the audience and send the rest of the band members scurrying for cover. But with that unpredictable tension came a certain excitement and unpredictability that was fuel for the fire of all Seldom Scene stage shows.

In his forty years in the bluegrass music, John was unique and fortunate to have been the catalyst in forming two landmark bands. The first came by accident, literally.

On July 4th, 1957, Buzz Busby, a legendary Washington area mandolin player and tenor singer, was contracted to play a gig at a local night spot. When he was involved in an automobile accident and was unable to make the show, the group’s banjo player, Bill Emerson, started making phone calls and arranged for Charlie Waller and John to fill in. The resulting sound was pleasing to everyone that they decided to give themselves a new name and continue playing together.

Never one to follow trends, John felt that a band from Washington DC should choose a name that reflected its own heritage and not use a ‘So and So and the Mountain Boys’ or some other name that suggested they were from somewhere they were not. The name John chose was The Country Gentlemen, then a very urbane name for a bluegrass band. His former colleague in that group, Charlie Waller, continues to tour and perform with that band

Due to the interest of Bill Emerson and John, tunes that were country, pop, blues, jazz, and classical became fair game for the Country Gentlemen who became noted for pushing the envelope of the existing bluegrass repertoire.

John said, “There were enough versions of ‘Blue Ridge Cabin Home’ and ‘Cabin in Caroline’ to go around. He was looking for something different. Hence the Country Gentlemen’s song bag included John’s jazzy mandolin interpretation of ‘Sunrise’, Bob Dylan’s ‘Its All Over Now Baby Blue’, and a mandolin version of the theme from the movie ‘Exodus’.

John also recognized the importance of the Folk Revival in the early 1960s and spent a considerable amount of time at the Library of Congress, researching material and achieving considerable success in composed melodies for old poems he found during his research. Songs entering the Country Gentlemen’s repertoire in this manner include the classic, ‘Bringing Mary Home’ and ‘A Letter to Tom’. In addition to collecting and arranging old songs and poems, John composed and dedicated to his wife Nancy, ‘The Traveler’, and the haunting ‘Victim to the Tomb’, along with many others.

But by the late 1960s John had tired of all the traveling necessary to sustain a bluegrass band. “I just got tired of saving up to go on tour,” he said. In 1969 Duffey left the Country Gentlemen with no intentions of performing again. During the 1969 to 1971, John operated a musical instrument repair shop.

But in 1971 John again found himself involved with music business, and again, by accident. He was joined in a informal group by former Country Gentlemen bassist Tom Gray, and by Ben Eldridge, Mike Auldridge and John Starling. This band would go on to be known as the Seldom Scene.

But in 1971 John again found himself involved with music business, and again, by accident. He was joined in a informal group by former Country Gentlemen bassist Tom Gray, and by Ben Eldridge, Mike Auldridge and John Starling. This band would go on to be known as the Seldom Scene.

As the name implies, this group of musicians did not form with the intention of touring and playing music for a living. All the members had day jobs and simply wanted an outlet for their music. John said it was, “Sort of a boy’s night out, like a weekly card game.” The group started out in a member’s basement, playing for fun, and then moved to the small Red Fox Inn outside Washington, DC. The group would later move across the Potomac River to a weekly Thursday night time slot at the Birchmere, in Northern Virginia.

Not being driven by the financial contraints to adhere to any of the rules normally associated with a professional touring group, the Seldom Scene did the music they wanted to do the way they wanted to do it. John’s feeling was that “If people enjoy what we do, fine. If they don’t, that’s okay, too.” With this freewheeling attitude, the group continued to stretch their musical reach by recording tunes from the Eric Clapton catalog, ‘Lay Down Sally’ and ‘After Midnight’, to long improvisational numbers with extended jams like ‘Rider’.

This continuing tendency to incorporate influences from outside of the traditional sources made it easier for the urban audiences around Washington to identify with bluegrass. It also expanded the group’s popularity to far beyond the doors of the local DC club scene.

And the experimentation continued. In the weeks before his death, the current band was in rehearsals for their next recording project and were working on an arrangement to the Muddy Waters classic, “Rollin’ and Tumblin'”.

John Duffey and the Seldom Scene continued to be active up to the end, playing in Englewood, New Jersey, just days before John’s death.

John Duffey’s influence on generations of musicians cannot be overstated. Noted music historian, Dick Spottswood, said, “There hasn’t been much that’s taken place in bluegrass since the 1950s that he hasn’t influenced one way or another.”

© Sing Out! magazine. All Rights Reserved.

DCBU thanks iBluegrass Magazine, the Seldom Scene, and Sugar Hill Records for the use of these images.

All images appearing on this page belong to their respective owners.