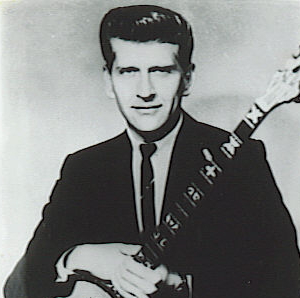

Walter Hensley – The Banjo Baron of Baltimore

By Tina Aridas (with permission)

That night back in April of 1959 when Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys played Carnegie Hall (along with Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim, Jimmy Driftwood, and Mike and Pete Seeger, among others). Curtis Cody, who was guesting on fiddle for the Baltimore-based bluegrass band, peeked through the curtains before the start of the show. The elegant hall was packed with Northern folk-music fans, as the first bluegrass group ever to perform at the elegant and historic concert hall, more accustomed to playing in bars in and around Baltimore, paced nervously backstage.

That night back in April of 1959 when Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys played Carnegie Hall (along with Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim, Jimmy Driftwood, and Mike and Pete Seeger, among others). Curtis Cody, who was guesting on fiddle for the Baltimore-based bluegrass band, peeked through the curtains before the start of the show. The elegant hall was packed with Northern folk-music fans, as the first bluegrass group ever to perform at the elegant and historic concert hall, more accustomed to playing in bars in and around Baltimore, paced nervously backstage.

Curtis turned to banjo player Walter Hensley and said, “Walt, I don’t think they’ll like us a bit.” Walt recalls that his legs “were like Jell-O, and we had to play the fastest song we knew.” But when Walt, with legs shaking, stepped out onto the stage before the assembled audience at Alan Lomax’s Folksong ’59 concert, Curtis recalls that “he played something on the banjo, and they tore that place up.”

Curtis Cody wasn’t alone in his assessment of the band’s performance and the crowd’s reaction. “There is true folk magic in every note Walt plays,” according to Alan Lomax. Neil V. Rosenberg, in his book Bluegrass: A History, reports that “all agreed that of the various groups in the concert, Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys were the hit of the evening.” Years later in an article in Bluegrass Unlimited by Tom Ewing, Earl Taylor recalled, “When we would end a number, I knew that it would take five minutes before we could go into another one – that was how much rarin’ and screamin’ and hair-pullin’ there was.” The recording of that concert, released as an LP later that year on United Artists (“Folksong Festival at Carnegie Hall” – UAL 3049), influenced a generation of young musicians and new fans, many from urban areas in the North who were exposed to bluegrass for the first time.

Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys’ hard-driving “Baltimore-style” bluegrass, the sound that whipped the audience into a frenzy that one evening in NYC and regularly in clubs in and around Baltimore, was right up there with Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs, according to Del McCoury, who at the time lived in nearby York County, PA, and was a frequent visitor to the vibrant Baltimore scene.

Walter Hensley was, and still is, one of the finest practitioners of that Baltimore style of bluegrass and some say one of the greatest banjo pickers ever. Indeed, he has been called the “Banjo Baron of Baltimore”. His driving banjo and inventive licks earned him the first solo banjo LP ever to be recorded on a major label and has elevated his name to the status of cult legend among banjo players and aficionados of that high-wire style of banjo playing. If there was a roster of influential and innovative banjo players, Walt would be on it, but his name is unfamiliar to many bluegrass musicians and fans. He is a stylistic pioneer, but, as bluegrass writer Jon Weisberger writes, Walt has been “criminally under-appreciated.” Bill Monroe biographer Richard D. Smith says that “Walter remains one of the terribly underrated greats of the 5-string.”

Walt was born in Grundy, Virginia, in 1936. His father, Finn, after a stint in the Navy, moved his family to a coal camp in Pike County, Kentucky, where he had gotten a job working in the coal mines. Sometime during that period he ordered Walt and his older brother Jim instruments from the Montgomery Ward catalog: Walt got a banjo (“a 24-dollar-job,” says Walt) and Jim got a guitar. “I had to learn off the radio,” recalls Walt. “Didn’t have any records or anything. I just kept messing with the banjo roll. Drove my Dad crazy because he worked in the mines, and he’d have to get up at four in the morning. He said, ‘If you’re going to play that thing, I want you to learn it, but go out to the barn’.” Replacing broken fingerpicks and strings was possible only when someone who had a car was going to town 35 miles away, and could bring some back. So Walt sometimes made fingerpicks out of PET Milk cans (“They were not all that bad; better than nothing if nobody was going to town,” says Walt). To replace broken strings he sometimes cut the insulation off blasting wire that was used for setting off dynamite in the mines, then tuned it down low enough so it wouldn’t break when played.

By 1952 Walt’s banjo-playing earned him (along with his brother Jim on guitar and mandolin) work on a radio show on WLSI in Pikeville, Kentucky, with Hobo Jack Adkins and the Kentucky Pals. At around the same time, Walt was filling in as banjo player with bluegrass pioneers the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers for several show-dates. Walt moved to Baltimore in 1956 and, during a stint in a rockabilly band called the Black Mountain Boys, met Earl Taylor. “Earl had just come back to Baltimore after playing in Jimmy Martin’s band,” Walt recalls, “and wanted to start his own band. He sat in at the Cozy Inn where I was playing and asked me if I wanted to join, and I said, ‘Yeah’.” So in early 1957 Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys was formed, and included Earl on mandolin, Walt on banjo, bassist/comedian Vernon “Boatwhistle” McIntyre, and Charlie Waller (who later that year went on to co-found the Country Gentlemen) on guitar. Within a year, Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys had recorded two songs for the newly formed Rebel Records: “Stoney Mountain Twist” (a composition by Walt) and “The Children Are Cryin’.” (In 1962 a new version of ‘The Children Are Cryin'” retitled “Calling Your Name”, along with “Stoney Mountain Twist” became Rebel’s first bluegrass single.)

In 1959, the same year as the Carnegie Hall concert, the band recorded an album for United Artists, and Mike Seeger made a (soon-to-be-influential) live recording of the band for Folkways Records in a room upstairs at the famous (some might say infamous) 79 Club on Cross Street in Baltimore, where the band had been playing a seven-nights-a-week gig. The band then moved west to Missouri, but after a brief stay Walt came back to Baltimore and joined the Country Gentlemen in 1961, who at that time included Charlie Waller, John Duffey, and Tom Gray. But less than a year later Walt quit the band to re-join Earl, who had left Missouri and was moving to Cincinnati. The band signed with Capitol Records and, the following year, recorded “Blue Grass Taylor-Made”. During the recording session, Walt was asked by Capitol to record an album under his own name. Shortly afterward, he left the band, recorded “5-String Banjo Today” for Capitol, and formed his own band, the Dukes of Bluegrass.

But these were tough times for bluegrass musicians. The market for bluegrass music was already languishing after Elvis-fever swept the nation. Beatlemania was too hard a second blow. Capitol stopped pressing bluegrass albums and put its resources into manufacturing Beatles records. Walt left Cincinnati and moved back to Baltimore, where he worked a variety of non-music jobs and played only weekend music gigs, even completely laying off performing bluegrass in public for a while, although the Dukes of Bluegrass disbanded and reformed a couple of times during this period (and included Jim McCall in the early 1980s, as well as Leon Morris, and Bill Slotzhauer). Walt consistently remained an important musical influence in Baltimore bluegrass.

In the early 1990s Walt moved to Pennsylvania, and his public performances were limited to occasional festivals with Vernon McIntyre’s Appalachian Grass, (led by the son of Stoney Mountain Boy Vernon “Boatwhistle” McIntyre). It was in the summer of 1999 that he and James Reams met at the Riverside Bluegrass Festival in Groveton, New Hampshire, where Walt was playing with Appalachian Grass and James was playing with his bluegrass band, James Reams & The Barnstormers. Walt and James talked some and listened to each other play, and hit it off. James and Walt saw each other over the next couple of years at festivals and bluegrass venues where the two bands were playing, and continued the personal and musical friendship. They shared a similar background, although a generation apart: both were from rural Appalachia and migrated to an urban area as young adults (James was a native of eastern Kentucky who had moved to New York City in the 1980s). And James Reams & The Barnstormers played a hard-driving style of bluegrass that Walt could relate to.

James was keeping a busy musical schedule, but he kept in touch with Walt. In the summer of 2001, late one night when James got back to NYC after one of the band’s shows, he started thinking about Walt’s banjo playing again. Here was a legendary banjo player – indeed, one of that first generation of bluegrass musicians who had helped to shape the music’s sound – yet Walt hadn’t been in a recording studio for more than 25 years. But James picked up the phone and called Walt. It was time to get him back into the studio.

The logistics of the rehearsals were tricky: James, along with bass player Carl Hayano and mandolin/fiddle player Mark Farrell, took repeated day-trips in the fall of 2001 to Walt’s home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to go over the material. There were lots of long phone calls. When the recording date was set, Walt would have to come to NYC and record it all in one weekend. Accompanied by his teenage son, Dale, Walt came to New York in February 2002 for the sessions (and somehow squeezed in some of the sights of NYC). James recalls, “During the sessions Walt was like an otter in a lake: just as nimble, and performing banjo acrobatics.” Recorded live-in-the-studio Walt’s banjo playing hadn’t lost any of impeccable timing, punch, drive and inventiveness. The results were the 2003 Copper Creek release “James Reams, Walter Hensley & The Barons of Bluegrass” (CCCD-0214). The session included James Reams (guitar), Walter Hensley (banjo), Carl Hayano (bass), Mark Farrell (fiddle, mandolin), Bob Mastro (fiddle) and Barry Mitterhoff (mandolin).